In the beginning

There was this bar in Ithaca.

Like most bars in Ithaca, it catered to college students: Cornell and Ithaca College and that meant beer. A lot of it. Mostly Bud and Miller or something German or Dutch in a bottle.

I don’t remember the name of the bar other than the fact that is was not the one where Rod Serling hung out in the summer time when he was writing Twilight Zone scripts.

But I do remember that one early May afternoon in 1972 when the early crocuses were still frozen solid to the ground for blooming too early, I heard about this bar where the owner was serving beer he had made himself in a back room.

This was unheard of. Mind-boggling. But the beer was awesome!

The next time I went back, the bar had been closed by the alco-cops because he didn’t have a license to make beer.

Summer came on a weekend in Ithaca that year.

I graduated from Cornell. Left town Never stopped thinking about that handmade beer.

Craft was not even a work then. No one had every heard of a micro-brew.

Bleeding edge

Fast forward to 1987.

When I left Silicon Valley and moved to Moraga east of San Francisco, the word “craft “still applied mostly to beads, pottery, scrapbooking, and macramé.

But, that year, we heard about a “micro-brewery” that had opened up in nearby Walnut Creek. The Devil Mountain Brewery made beer on site and a had a nice tasty bar menu.

It became a regular place for us, but it was never full. No one really had any idea what the concept was all about.

By about 1995, it was out of business. The brand still lives in the portfolio of some megacorp.

The market was not ready.

Boom!

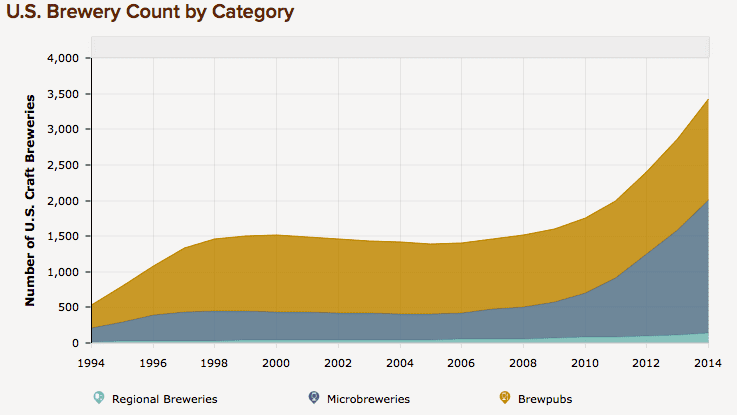

The fact that the chart at the top of this article begins in 1994 indicates that there was little going on before then other than the struggles of hardy pioneers like Sierra Nevada and New Albion.

Then came 2008 and the category boomed and “craft” became synonymous with beer made in mostly small lots with passion, dedication and a solid does of quirkiness and personality.

Craft began to mean quality and drove the artisan movement beyond beer

The growth of craft beer raised the consumer consciousness about the value and quality of non-mass-produced beer. Craft became synonymous with handmade, handcrafted, and authentic. It implied that there was a person with a passion behind the product instead of a faceless corporation.

The concept got people to thinking. If it could be so successful with beer, what else?

The growth in the craft concept then spurred the use of “artisan,” especially for spirits. Cider, mead, and soft-drinks seem content with wither craft or artisan. Vintners, on the other hand, have — for decades now — been fighting the quality battles of small, individual-driven wines versus the Gallos and Constellations of the world.

For their part, these small wineries have not given much thought to distinguishing themselves with a “craft” or “artisan” designation.

The sole exception to this has been the Garagistes of Paso Robles who have created a category of their own patterned after the small French winemakers making small lots of wine in their garages.

Growing pains…

Which brings us to the present day. The wild success of craft and artisan beverages has brought growing pains to the people behind the products. Founders are realize that staying in business requires more than the ability to make an awesome beverage.

Just like that bar owner/brewer in Ithaca who didn’t realize that regulatory matters trumped quality, today’s craft beverage masters haven’t all realized the need to think about accounting, legal issues, insurance (worker’s comp what?), partnership agreements, employment management …. headache after headache.

… Big money …

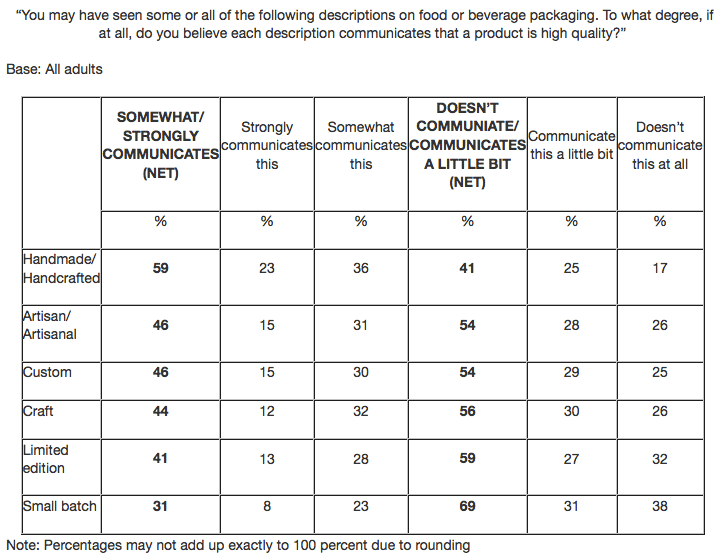

Success has also brought deep pockets looking for a piece of crafty action. After all, word choice can change perception

Source: New Harris Poll Looks at “Craft”-y Marketing Language Right-click chart for larger view.

… Uncertainty …

With the deep pockets comes the uncertainty of whether large beverage corporations will dilute the perceived value of “craft,” “artisan,” and other terms.

In the wake of some very high-profile acquisitions of craft beverage companies — such as Heineken’s recent $1-billion purchase of 50% of Lagunitas — there is worry among c0nsumers that their favorite beers and quirky brands will go the way of wine in a box.

After all, the vast majority of small, highly acclaimed winery acquisitions by large corporate refinery wineries has resulted in little m0re than plonk whose best asset is that it will not cause permanent harm.

I had the opportunity to talk with Lagunitas owner Ron Lindenbusch during the California Craft Beer Summit in Sacramento last Friday. While not going into great detail about the merger agreement, Ron says he is comfortable that his attorneys have created an agreement that will prevent Heineken from affecting his brewing of Lagunitas … or taming his (and his brewery’s) quirky nature that its fans love.

… And an identity crisis

Finally, this evolution and growth have prompted introspection as well as legal battles over the definition of craft, hand-made, artisan and other terms that consumers tend to see as indicators or quality and superiority.

Can craft be big?

Does it still have to be three brothers and their Mom having a grand opening like Sonoma Springs dis this past weekend in the town of Sonoma?

Or are craft and artisan defined by the overlapping of many different things like a giant Venn diagram including:

- Small beginnings (think garage) by,

- Passionate,

- Hands-on

- Entrepreneurs,

- Risking their own resources,

- Dedicated to,

- A dream,

- That remains true to their vision.

There are probably more than these eight characteristics, but each, if combined in sufficient quantity, add up to authenticity which remains the foundation of craft and artisan.

Written by Lewis Perdue of Craft Beverage Insight